(Note: we're using "reduce" strictly in the computer science sense in this article, lest anyone be confused.)

Flux is awesome but there are still numerous open questions. One of the toughest, which everyone has to face sooner or later is: where do API calls belong?

I am not really sure whether anybody has found a proper answer to this. Flux is agnostic: as long as your API call dispatches a new action, you are doing it "right".

I remember when I first starting using Flux, I tended to put all my API calls in Stores because this seemed most natural to me. However, after spending some time reading articles and tweets, I found that most people prefer putting the code in Action Creators. I have never been a fan of this approach. I can't shake the idea that domain logic belongs in a single place, namely the Store.

Meet Reducer, please

Lately, two concepts have taken the Flux community by storm: Atomic Flux and Reducers. If you don't know anything about Reducers, stop now and read my previous article first. The idea has been heavily popularized by Dan Abramov's Flux implementation, Redux (though we are not even sure yet if we should be calling it Flux).

I really love the idea of keeping the application state in single Atom, as well as Stores being just functions that reduce Actions to State. However, reduce in functional terms has one important requirement: the Reducer must be pure and can't have any side effects.

This is more than just semantics. If you make your Reducers pure, this has many benefits. It's pretty easy to log every action, and you will basically get features like replay and undo/redo for free. Also, when every Reducer is pure, it enables a killer feature that wasn't really possible in original Flux implementation: hot-reloading of Reducers. Dan Abramov was a pioneer in this area and it's one reason why Redux is so popular.

Let's say you are implementing a todo list app. When the user clicks on a todo item, it removes the item from the list. However, after you implement this, you change your mind and decide to leave that item in the list and turn it red. With hot reloading of Reducers, you don't need to hit the refresh button and add those todos again. You just change your implementation and all the removed items suddenly appear again in the list. In my view this is great developer experience.

Also, just imagine how awesome it is to test pure functions. There are no external dependencies and no mocking. You just need to prepare some data, call the function and expect some result.

So far, so good. Everybody is super-excited, right? It always looks so simple in some demo app. I still remember the first time I saw Facebook's Flux chat example showing how to use waitFor. In my opinion this is one of the worst examples I have ever seen. The use case in this particular example is really artificial and does not really show why waitFor is needed.

Unfortunately pure Reducers have the same problem. They sound really cool, but when it comes to real-world use cases, you discover pretty quickly that it's basically impossible to have Reducers without side effects. API calls, logging, caching, routing, local storage... any time your app interacts with the world there is potentially a side effect. However, these side effects are inevitably tied to your application's logic, which ideally should be in one place.

It's also important to recognize that in most cases we need application state to parametrize the side effect. For example, we might want to send an API call to get a list of items parametrized by page. And what about testing? We definitely want to test that we are calling the right API endpoint with the right parameters.

It's sad, but I would rather give up all the killer features of pure Reducers like hot-reloading just to have my domain logic in one place and easily testable. I have found that keeping API calls in Reducers has such strong advantages in terms of maintainability that it's not really worth putting them into Action Creators just to improve our DX.

Reducing state... and side effects

Ideally we would like to keep our side effects in Reducers while preserving their pureness.

This sounds like an oxymoron: if the Reducers have side effects then by definition they are not pure. However there is a way: reduce both state and side effects.

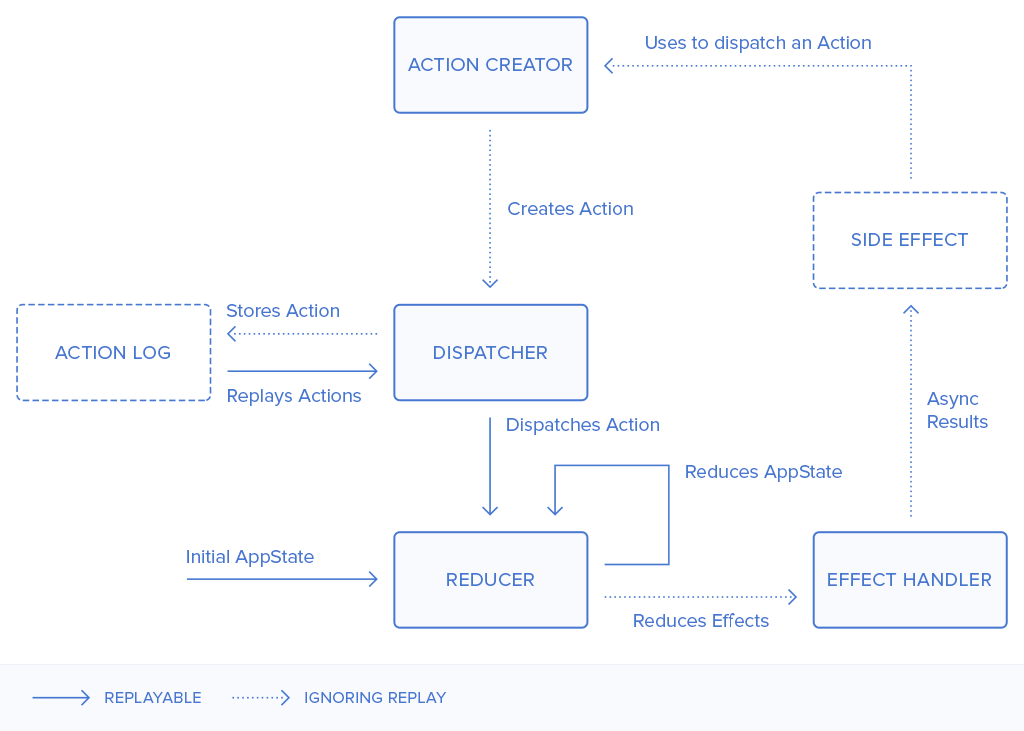

Potentially, API calls can be expressed as an Event or Action with some payload. This doesn't apply only to API calls but to any side effect in general. We can thus describe a Reducer as follows:

reduction = actions.reduce((reduction, action) => reduction, initialReduction)

...where reduction is {state, List<Effects>}. In other words, instead of reducing only application state, we reduce a pair of application state and a list of Effects. Once all the reducers are processed, we can have Effect Handlers that take each Effect (composed of type and payload) as input and produce a side effect that potentially dispatches another action.

For example, our action might include an Effect that retrieves a list of todos from the server asynchronously. Our Reducer would still be pure since it would just reduce the Effect into a list for later processing. Once the Reducers have done their job, the Effect Handler would pull that Effect out of the list, call the API and dispatch a new Action with the list of todos as its payload.

The cool thing is that we can simply ignore this step in replay process. We don't have to worry about the side effect of the first Action since the second Action (with the appropriate payload) is in the Action Log as well. That's right, we have recovered our beloved time travel!

Writing tests with this approach is also pretty straightforward: we can write tests as before. Because the reduction contains a list of effects, it's easy to check if handling an Action results in specific side effects with specific payloads. It sounds like we might have achieved our original goal: a pure Reducer capable of API calls and other side effects.

Some have argued that if you keep your API calls in Reducers/Stores, it is too easy to misuse the callback and directly mutate application state without dispatching a new Action. This is simply not possible with our approach, because the Reducer takes only the reduction and an Action as parameters. It's not even possible to do action chaining (say goodbye to the "Cannot dispatch in the middle of a dispatch" Exception) since it doesn't have access to the Dispatcher.

On the other hand, the Effect Handler has only the Effect itself and the Dispatcher as parameters, which means that direct state mutation is impossible there as well. This approach also prevents users from Flux worst practices such as treating an Action as a Command instead of an Event.

But enough reading, you might be keen to try out this approach on your own. Because I love coding as much as you do, I have prepared an example. By they way, the screencast above uses this boilerplate with a few minor modifications. Be aware: it's not a framework, it's just a fully hot-reloadable example of Atomic Flux with an innovative approach to handling side effects.